Arctic Skua.

Because the Austin Sheerline ambulance had been abandoned, the police were called. Customs and quarantine officers soon joined them. The ambulance was traced back to Hull, to an address on the River Humber. The paper-trail ended there. In the glove box they’d found a hardcover copy of The Collected Poems of David Gascoyne, E.W. Elwood’s Badger Husbandry, and a single crow feather. Eventually the ambulance was towed away to the Water Police compound.

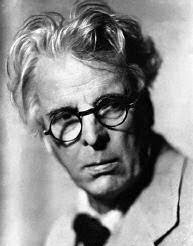

When W.B. Yeats and Geoffrey Hill entered the Angler’s Rest, the Sons of Zebedee stood against the wall, watching Hill closely. Geoffrey delighted in reaching into the inside pocket of his coat. On seeing this, the Sons bolted for the door. Yeats turned to Geoffrey: “I respect a man who can scatter fools with even the slightest suggestion of impending doom,” he said.

John Berryman was pissed and in no mood for poets or poetry. “I am taking the waters from the wellspring of a black-and-white-collared heart,” he said, too slowly, when W.B. and Hill walked into the room. “Spoken like a true gentleman,” Yeats said. “Now, finish your pint. We have serious work to do.” “And what that might be?” asked Berryman. Geoffrey Hill took the pint from Berryman’s hand. “You know as well as I do that no-one has any idea until it happens,” he said. “Isn’t that right, W.B.” he said, but Yeats had left the room.

Lucinda Williams was on her mobile. Reception at The Afterglow was patchy, so she’d gone down to the wharf. She’d called her manager in Nashville, and he was telling her that Emmylou Harris, Rawlings and Gillian Welch had gone to Australia on a mission to save a red fish. He then said that other musicians had joined them. Some were on their way to support the Release All Waggas cause, and others were going to try and kill as many as they could. The list of singers, songwriters and bands was straight out of the country music Hall of Fame: The alternative country-punk band Drag the River had left on a huge dredging barge; Townes van Zandt, Guy Clark and Steve Earle were flying down in Townes’ Nord Noratlas; John Prine was coming with Dave Alvin and the Guilty Women; Steve Forbert was bringing his saltwater swoffing gear; Waylon jennings was on his way with Blaze Foley; Dolly Parton and Patsy Cline were meeting up with Linda Ronstadt and Nicolette Larson in L.A., then flying down. It was going to be very busy time.

Lucinda Williams folded her phone and looked out at the Red Oblong. “What a circus,” she said. A parasitic jaeger looked down at her from its lookout on a wharf-lamp. It sharpened its beak on the lamp cover. It looked sideways into the harbour. “Blood,” it said, and went knifing off into the sun.

Back at the Angler’s Rest W.B. Yeats was recruiting men to help him unload a great container of Wagga-rods and reels that had arrived on the train from Sydney. They’d been shipped all the way from Sweden. Being a Nobel Prize winner, W.B. arranged to get the best Swedish rods made up specifically for Waggafish live baiting, and he also got an amazing deal on the purchase. The Sons had come back into the bar and this time Yeats talked them into helping him unpack the rods. He told them that seeing they were mentioned in the Bible as fishermen they should have the first of the red ‘armbreaker’ rods. Yeats walked over to the post office and sent a message to James Joyce by email. He told Joyce to leave Paris immediately and to bring Ernest Hemingway as well. Yeats knew Hemingway was the perfect man for the job, he’d help organise this rabble at the Angler’s Rest and bring some steel into the hunt. He didn’t quite know what use Joyce would be but at least he’d get Hemingway to come. W.B. couldn’t believe he hadn’t thought of Hemingway before this.

Things were happening, and although W.B. spoke ironically of the American singers he thought the publicity they might create could be put to use. He was starting to hatch a plan, it would take all his wile to swing but once certain things fell into place the Waggafish would be a dying species. He would set up a fleet of boats, they’d confiscate all the trawlers in the surrounding towns from Woy Woy to Brooklyn for a start, and they’d have boats trawling for squid, they’d have mesh-nets catching slimy mackerel. He wasn’t counting on Shelby and Greene to come up with a re-usable live bait: and besides he still couldn’t tell who they were working for. Was Seidel behind them? Were they just lunatics or did the presence of the Red Oblong indicate that there was something more substantial going on?

There was a racket going on down at the Brooklyn Fishermen’s Co Op. Bill was abusing Auden and a group of ex-Waggaists had gathered around, yelling “Fight. Fight. Fight.” Auden had no idea how he’d got to Brooklyn. One minute he was on The Island, in the cage with Jamie Grant, dishing out a hiding with a plank, and the next he was shaping up against Bill Wisely. Life, friends, was not boring. And now a bird was coming straight at his head. It was an arctic jaeger, flying at an incredible speed. Auden’s sight was failing and he didn’t see it approaching. Suddenly, Bill swung around and grabbed a plank he had sitting beside his old Qantas bag. It happened fast. Bill held the plank as if it were cricket bat, took a savage swing and collected with the jaeger. The sound made people turn away. Bill’s eyes were wild, he glared at the crowd fiercely and said “Yeah, well, who wants a fucking fight now?” There were blood stained feathers everywhere and Auden kicked the mangled bird aside. It was truly a tragic spectacle. W.B. Yeats saw the whole thing, he didn’t raise a hand, but during this frightening episode he was making notes with a pencil and notebook.

G. Lehmann, the Front

G. Lehmann, the Front